Abstract:

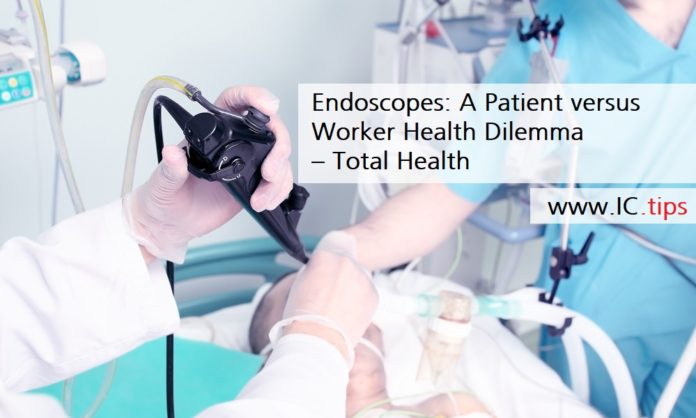

As the public becomes more aware of the possibility of becoming infected with drug resistant pathogens from inadequately reprocessed endoscopes when they undergo endoscopic procedures, our duties increase as professionals because we are dedicated to keeping the public safe by instituting all facets of infection prevention. Reprocessing endoscopes – cleaning and disinfection – is an onerous process that requires a great deal of physical exertion, time, and attention to microscopic detail and puts those performing the task at risk of exposure to occupational illness and injury. In light of clinical public health recommendations to increase preventive screening procedures that use endoscopes, these risks to both patient and worker also increase. Therefore, it is important to take a “total health” philosophy to protect patient and worker while not compromising the health and well-being of one versus the other.

Main Article:

As a public health practitioner with focus on occupational safety and health – specifically worker risks associated with infectious disease – on many current events, I find myself at odds with… myself. This is a common occurrence, but for the purpose of this first piece in a series of many, I will focus on my dilemma with endoscopes.

From a public health point of view, endoscopy is done to probe, diagnose and treat a host of conditions and diseases, ranging from gall stones to cancer. Devices like colonoscopes and duodenoscopes are used by gastroenterologists to reduce morbidity and mortality to save lives. The more frequently they are used for preventive and therapeutic reasons to catch something early, the less they need to be used for surgical interventions for advanced, higher risk cases. The more complicated the technical design of these scopes are, the better they are navigating tight turns, obtaining smaller samples (biopsies) and due to better resolution of the cameras, the easier it is to identify early stage problems, reduce complications, and improve recovery time in patients. Those translate to benefits for you and me, our friends and families.

From an occupational safety and health point of view, the more frequently these high tech endoscopes like these are used, the more they need to be processed and reprocessed, dismantled, brushed, cleaned, disinfected, and safely transported and stored. If this is done well, if this is done to prevent any contamination or buildup of biofilm that may affect the patient it is used on – it takes a great deal of time, physical effort, and attention to detail. Most employees who clean endoscopes prior to disinfection (without proper cleaning, adequate disinfection cannot be achieved) use very long, skinny, flexible brushes that are designed to go the length of the endoscope channels – sometimes up to 230 cm which is over 7 feet!1

If the facility is lucky enough to have an endoscope cleaner and reprocessor machine, this process can be automated; if not, it is done by hand using a channel cleaning brush and detergent.2 It entails the employee to torque their full arm and shoulder repetitively, in and out, in and out, to do the job well. It requires close contact with blood, body fluid, and human tissue and requires the close adherence to technique, process, and use of PPE. This process can be so intricate that some manufacturer’s instructions for use (IFUs) for reprocessing scopes are 100 or more pages long. This process, if not followed, puts the worker at risk of exposure to infectious disease, bloodborne pathogens, harsh detergents, and hazardous chemicals like disinfectants, as well as repetitive stress.

some manufacturer’s instructions for reprocessing scopes are 100 or more pages long

The very recently published January 2016 Senate Report Preventable Tragedies: Superbugs and How Ineffective Monitoring of Medical Device Safety Fails Patients is a detailed summary of findings from an investigation done when hundreds of patients were identified with antibiotic resistant infections following endoscopy with improperly cleaned and disinfected scopes.3 The report gives an extremely detailed account of the infections linked to closed-channel duodenoscopes and the order of events leading up to and including the investigation. It highlights 25 separate outbreaks in 10 different states and 4 countries and outbreaks infecting at least 250 people with life-threatening illnesses including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures alone. This lengthy report does not address worker safety and health.

As a testament to this issue’s importance, the CDC published a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report with an article highlighting the importance of colorectal cancer screening.4 As I read through it, my mind keeps whirling towards the issue of – more contaminated scopes, more reprocessing, more brushing, and more worker exposure.

The self-imposed internal conflict increases.

It is important to identify all sides of screening recommendations, for the patient, their provider, and the person responsible for making sure the procedure is done with a device that is safe and free from contamination. With all of our focus on screening for patient safety and public health, we have shifted the conversation away from the worker, putting them at risk of becoming a patient themselves.

workers may not have the tools they need to be successful.

Employees who process medical devices are often unsung heroes. They work behind closed doors in rooms that patients and often providers don’t see or experience. They work quickly to ensure that devices are cleaned, disinfected, and sterilized so that procedures can be performed, patients can be diagnosed treated, and hospitals can turn beds and profits. The work is physical and reliance on it being done well is high. These workers may not have the tools they need to be successful.

In the occupational safety and health world, we have a movement towards “Total Worker Health”. “Total Worker Health” is defined – by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as “policies, programs, and practices that integrate protection from work-related safety and health hazards with promotion of injury and illness prevention efforts to advance worker well-being”.5 This is an established concept and is designed to get at making all workers safer, like those identified above, by approaching their health at a programmatic, institutional level.

Given the movement towards increased numbers of endoscopic procedures, it means increased infectious disease risk to patients and workers alike. We, as an infection prevention profession, need to think about creating a “Total Health” environment. One that protects the patient and the worker alike. This may mean having more conversations with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), medical device manufacturers, consensus groups like ASTM International and AAMI, with us at the center rather than on the periphery looking in. We have the responsibility to be the voice of infection prevention for “total health”, not just one element, one device, one process, one person, or one nation.

References:

- Endoscopic Devices Product Catalog. Olympus. https://medical.olympusamerica.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Endotherapy_Product_Catalog.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2016.

- Ofstead CL, Wetzler HP, Snyder AK, Horton RA. Endoscope reprocessing methods: a prospective study on the impact of human factors and automation. Gastroenterol Nurs.2010 Jul-Aug;33(4):304-11.

- United States Senate HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS COMMITTEE. Preventable Tragedies: Superbugs and How Ineffective Monitoring of Medical Device Safety Fails Patients. January 13, 2016. http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Duodenoscope%20Investigation%20FINAL%20Report.pdf Accessed February 2, 2016.

- Joseph DA, Redwood D, DeGroff A, Butler EL. Use of Evidence-Based Interventions to Address Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening. MMWR Suppl 2016;65:21–28. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6501a5. Accessed February 12, 2016.

- Total Worker Health Web Resource. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/totalhealth.html. Accessed February 12, 2016.

Dr. Mitchell shares a wonderful “inside view” (pun intended) about a hidden world in infection control and prevention that so many of us do not even begin to understand. As a clinical and public health microbiologist, I can just envision MRSA, Psuedomonas, CRE, and other MDROs adhering and creating biofilms in all of those “tight corners and niches” on the diverse array of endoscopes, etc. It makes me sit up and take notice of this article in a way I hadn’t before! This is important that we all, healthcare professionals in all fields that contribute to Total Worker Health AND patient safety, educate others about these hidden issues not always obvious. I have been a passionate writer and speaker in regards to my own profession, Medical Laboratory Science, being sometimes hidden. Let’s all remember that not everyone understands these critical, lifesaving jobs and skill sets that are behind the scenes. And, let’s also remember that those who do these jobs may not always have the ability or the tools to even protect themselves. Great job Dr. Mitchell!