What is CCHF?

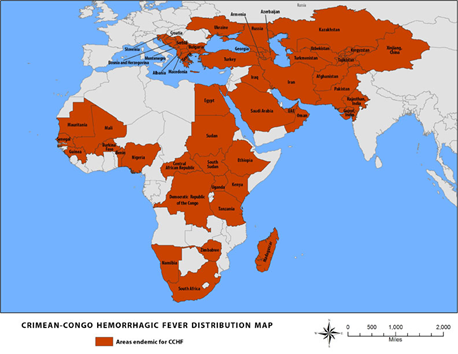

Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever virus (CCHFV) is a tick-borne virus belonging to the genus Nairovirus, family Bunyaviridae (Kuehnert, 2021). The disease was first described in the 1940s during an outbreak among Soviet military recruits in the Crimean Peninsula following World War II. In 1967, a virus that was isolated from an ill child in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo was found to be identical to the virus from the Crimean Peninsula, thereby coining the name Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CDC, 2013). Sporadic cases and outbreaks are now common across a huge geographic area, from western China to the Middle East, southeastern Europe, and throughout most of Africa (World Health Organization, 2023).

Figure 1. Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) Distribution Map.

Figure 1. Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) Distribution Map.

(Centers for Disease Control, 2014)

How are people infected?

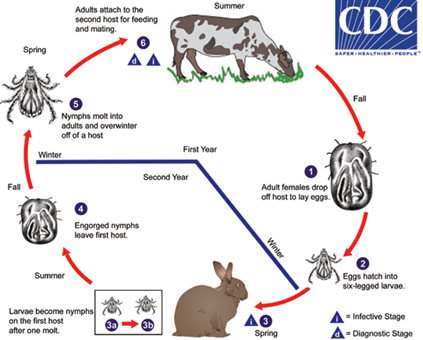

Unlike other viral hemorrhagic fevers, like Ebola or Marburg, CCHF infection occurs through the bite of Hyalomma tick – an ixodid tick that has a hard-outer shell – or through direct contact with infected mammals (mainly livestock) or their contaminated tissues and bodily fluids. People at higher risk for CCHF are soldiers, farmers, forest workers, shepherds, butchers, slaughterhouse workers and veterinarians. Infected mammals may be asymptomatic and may transmit CCHFV during this period to ticks or other mammals. Human-to-human transmission can also occur from close contact with blood, organs, or other bodily fluids of infected individuals. Religious gatherings may also serve as means of transmission. During Eid-al Adha in July, there is an increased risk of animal-to-human transmission of CCHF due to animal sacrifice practices involving livestock in addition to travel around the holiday.

Following infection by a tick bite, the incubation period is about 1 to 3 days, with a maximum of 9 days. Symptoms include a sudden onset of fever, myalgia, neck pain and stiffness, backache, headache, sore eyes, and photophobia (sensitivity to light). Other symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, confusion, and depression. As the infection progresses, clinical signs include tachycardia, lymphadenopathy, hepatitis, and a petechial rash. Severely ill patients may experience kidney, liver, and pulmonary failure. The mortality rate is roughly 30%. Supportive care is the primary method of treatment for CCHF, which includes fluid balance and hemodynamic support. Studies have shown the sensitivity of the CCHFV to the antiviral drug ribavirin.

Figure 2. Life cycle of the two-host ixodid (hard) ticks. Adults are considered the diagnostic stage, as identification to the species level is best achieved with adults. An example of an ixodid tick of public health concern with this life cycle is Hyalomma marginatum, a vector of Crimean-Congo viral hemorrhagic fever.

(Centers for Disease Control, 2017)

Pathogenesis

CCHF pathogenesis is often compared with that of Ebola, which is why CCHF has been called “the Asian Ebola virus.” Like other similar hemorrhagic fever viruses, the virus affects the body on two levels; direct virus-induced cytopathic damage to the cells of organs with endothelial deterioration are accompanied by activation of the immune system and release of cytokines, chemokines, nitric oxide and other mediators that results in programmed cell death, stimulation of the coagulation cascade with development of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and multiorgan failure (Sudeck, 2018). Cellular targets are phagocytes, endothelial cells, and hepatocytes.

Figure 3. This historic 1969 image, depicts a hospitalized isolated male patient, lying in a prone position, who was diagnosed with Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (C-CHF), a tick-borne hemorrhagic fever with documented person-to-person transmission, and a case-fatality rate of approximately 30%. This widespread virus has been found in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. Note the blotchy, cutaneous lesions scattered over his mid-, and lower back, and buttocks.

(Centers for Disease Control, n.d.)

CCHF virus infection can be diagnosed by several different laboratory tests, including:

-

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- antigen detection

- serum neutralization

- reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

- virus isolation by cell culture (WHO, 2022)

Infection Prevention for Healthcare Workers

If a patient is suspected to have CCHF based on signs, symptoms, travel history, and other potential epidemiologic factors, it is crucial to isolate them as soon as possible, select appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) that is used for viral hemorrhagic fevers, and incorporate other engineering and administrative controls to protect staff and patients.

The Centers for Disease Control recommends placing a patient in a single-patient room and emphasizes the use of standard precautions in addition to transmission-based precautions, hand hygiene, and barrier protection against blood and body fluids upon entry into room (personal protective equipment) and appropriate waste handling. N95 or higher respirators should be worn when performing aerosol generating procedures. Healthcare exposure and transmission has been reported, further emphasizing the importance of prompt identification, use of PPE, and implementation of safety precautions. For example, in 2009, two healthcare workers in Germany became infected with CCHF after caring for a CCHFV-infected U.S. soldier who had been in Afghanistan (Conger, 2015). Transmission was thought to have occurred during bag-valve-mask ventilation, breaches in personal protective equipment during resuscitations, or bronchoscopies that may have generated aerosols when managing pulmonary hemorrhage.

Climate Change and the Risk of Geographical Spread

Thus far in 2023, numerous countries have reported upticks in CCHF. In Iraq, 377 cases have been reported in the first six months of this year (Iraq, 2023). In Afghanistan, 422 from 31 provinces since the beginning of 2023 (Afghanistan, 2023). Ticks infected with CCHFV were first identified in Spain in 2010 (Crimean, 2022). Since 2013, there have been twelve confirmed human cases of CCHF, including four deaths in Spain, with the most recent cases in July 2022. Other countries that have reported cases or outbreaks in 2023 include Georgia, Pakistan, India, and Senegal. Because of the extensive geographical distribution of the tick, high fatality rate, and the lack of available vaccines or specific treatment or therapeutic options, the World Health Organization characterized CCHFV as a high priority pathogen. Environmental changes like high temperature, humidity, and precipitation coupled with livestock trade and increased international travel can expand the distribution of the Hyalomma tick to new areas, keeping humans at risk for increased exposure to CCHV.

References

Afghanistan: Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Cases top 400 in 2023. Outbreak News Today. (2023a, July 9). http://outbreaknewstoday.com/afghanistan-crimean-congo-hemorrhagic-fever-cases-top-400-in-2023/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013, September 5). Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/crimean-congo/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, February 12). Outbreak distribution map. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/crimean-congo/outbreaks/distribution-map.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, December 31). CDC – dpdx – ticks. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/ticks/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Details – public health image library(phil). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://phil.cdc.gov/details.aspx?pid=2315

Conger, N. G., Paolino, K. M., Osborn, E. C., Rusnak, J. M., Günther, S., Pool, J., Rollin, P. E., Allan, P. F., Schmidt-Chanasit, J., Rieger, T., & Kortepeter, M. G. (2015, January). Health care response to CCHF in US soldier and nosocomial transmission to health care providers, Germany, 2009. Emerging infectious diseases. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4285246/

Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever cases in Spain. Travel Health Pro. (2022, August 30). https://travelhealthpro.org.uk/news/651/crimean-congo-haemorrhagic-fever-cases-in-spain

Iraq reports 377 human CCHF cases in first half of Year. Outbreak News Today. (2023b, July 16). http://outbreaknewstoday.com/iraq-reports-377-human-cchf-cases-in-first-half-of-year-48703/

Kuehnert, P. A., Stefan, C. P., Badger, C. V., & Ricks, K. M. (2021). Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus (CCHFV): A silent but widespread threat. Current tropical medicine reports. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7959879/

Sudeck, H. (2018). Haemorrhagic fever in the field. Military Medicine Worldwide. https://military-medicine.com/article/3466-haemorrhagic-fever-in-the-field.html

World Health Organization. (2022, May 23). Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/crimean-congo-haemorrhagic-fever

World Health Organization. (2023). Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/crimean-congo-haemorrhagic-fever#tab=tab_1