Abstract

Recent public health concerns call for innovative strategies to better protect clients, healthcare workers, and visitors in the healthcare setting. Pathogens can be found on the hands of visitors upon entry and exit from the healthcare setting. Hand hygiene is the most effective and economical behavior to reduce pathogen transmission. Although hand hygiene is frequently mentioned to the public to address community-associated infections, the context rarely addresses the visitor’s role in transmission.

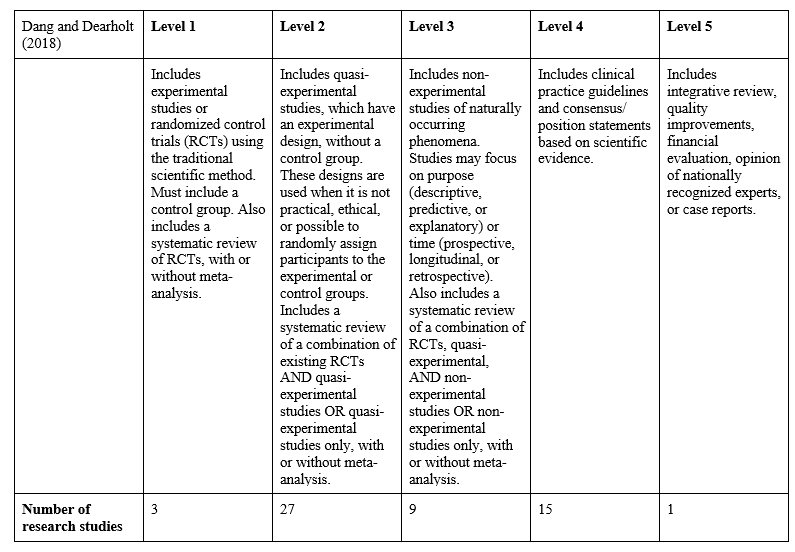

A literature review addressed the following evidence-based practice question: Does the implementation of healthcare visitor hand hygiene decrease pathogen transmission? Fifty-five studies spanning 17 years (2002-2019) were appraised using Dang and Dearholt’s (2018) five levels of evidence with Level 1 being the most stringent to develop and support our position on visitor hand hygiene.

Research studies found visitors’ hands become a reservoir and means of transmission if not adequately cleansed. Effective education increased the frequency of visitor hand hygiene, decreased pathogens found on their hands, and subsequently, decreased pathogen transmission in the healthcare setting (El Marjiya Villarreal, Khan, Oduwole, Sutanto, Vleck, Katz, & Greenough, 2020). Effective education led to greater visitor engagement, increased frequency of visitor hand hygiene, and may improve worker and client hand hygiene adherence.

This paper modifies the previously published Position on Healthcare Client Hand Hygiene (Morales, Puri, Knighton, & Greene, 2020) to address healthcare visitor hand hygiene. We present an affordable, practical, effective, acceptable, safe, and equitable evidence-based multimodal strategy.

Definitions

Hand hygiene: An inclusive term for the practice of cleansing hands, which includes hand washing, use of alcohol-based handrubs, or disposable wipes. Hand hygiene does not refer to surgical hand antisepsis performed in surgical settings (World Health Organization, WHO, 2009.

Hand hygiene supplies: Includes sinks, alcohol-based handrubs, and disposable wipes.

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs): Infections acquired while receiving treatment for other conditions within a healthcare setting (Centers for Disease Control, CDC, 2002).

Healthcare client: Recipients of care in any healthcare setting, including inpatient, outpatient, and/or long-term care settings. Referred to as client in this paper. The role of client hand hygiene was addressed in a separate paper (Morales, Puri, Knighton, & Greene, 2020).

Healthcare visitor: Persons in any healthcare setting, including inpatient, outpatient, and/or long-term care settings who are not receiving care and whose presence in the setting is transient. This includes the client’s family and friends or an outside vendor. Referred to as visitor in this paper.

Healthcare worker: Licensed and unlicensed employees in the healthcare setting, including inpatient, outpatient, and/or long-term care settings. Referred to as worker in this paper.

Background/Introduction

Recent public health concerns such as the coronavirus pandemic require innovative strategies to better protect healthcare visitors, workers, and clients. One strategy implemented during the Coronavirus pandemic has been to limit visitors in the healthcare setting. While this is an effective barrier to pathogen transmission, it has had serious negative emotional consequences for the client and workers, making it a less than ideal long-term solution. Harmful bacterial, viral, and fungal pathogens, including multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs), are found on human hands. These pathogens can lead to infection (Cao et. al, 2016; Mody et al., 2019). Hand hygiene is the most effective and economical behavior to reduce transmission of potentially harmful organisms and subsequent infection (Barnett et al., 2014; Tejada & Bearman, 2015). These infections are associated with long-term disability, increased length of stay, and higher risk of death (WHO, 2009). Pathogens in the healthcare setting may (Centers for Disease Control, CDC, 2019; Istenes, 2011).

Workers’ adherence to hand hygiene has recently been deemed a quality indicator with mandated public disclosure. However, limited information is available to the public as each state has different reporting criteria and not all states require HAI reporting (Cohen et al., 2014, National Council of State Legislatures, 2020). Any publicly reported hand hygiene metric will suffer because the credibility of various methods has not been established, leading to distrust of the data (Ellingson et al., 2014). For example, there is no national standard for the optimal number of hand hygiene observations or which indications should be monitored (Chassin, Mayer, & Nether, 2015a; Chassin, Nether, Mayer, & Dickerson, 2015b).

the visitor’s role in pathogen transmission in the healthcare setting is rarely addressed

Although hand hygiene is frequently mentioned to the public to address community-associated infections, the visitor’s role in pathogen transmission in the healthcare setting is rarely addressed (Healthy People 2020, 2014; Wallace, Cropp, & Coles, 2016). Inadequate hand hygiene affects clients, workers, visitors, and the public (Seale, et al., 2016). However, it is imperative for all people in all healthcare settings to be vigilant regarding hand hygiene (CDC, 2016).

The transmission of pathogens via hand contamination between the healthcare setting and visitors is dynamic and reciprocal, asserting the role of the visitor in the chain of infection and contradicting the assumption workers are mainly responsible for transmission (Banfield & Kerr, 2005; Vaidotas et al., 2015). There are direct consequences for the population vulnerable to infections (Busby et al., 2015). Studies found visitors’ hands become a reservoir and means of transmission if not adequately cleansed (Srigley et al., 2014). While visitor hand hygiene is an obvious safety concern across healthcare settings, it is frequently overlooked and not routinely measured (Cheng et al., 2016). Healthcare reception areas have low hand hygiene adherence rates. As a result, visitors’ hands may be colonized shortly after entering a healthcare setting (Vaidotas et al., 2015; Sunkesula et al., 2017).

This paper modifies the previously published Position on Healthcare Client Hand Hygiene (Morales, Puri, Knighton, & Greene, 2020) to address healthcare visitor hand hygiene. It presents a formal, intentional, systematic appraisal of the evidence for visitor hand hygiene. Evidence-based practices (EBPs) are delineated to help you discover your key causes of visitor hand hygiene failure and to deploy a set of customized practices to address your key causes. Customized interventions to address your key causes may be the most important determinant of the intervention’s success or failure (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b). The role and responsibilities of all within the healthcare community are addressed. Finally, we promote a multimodal strategy to address your most significant issues.

Materials/Methods of the Interventions

Hygiene and infection prevention and control strategies have traditionally been nursing responsibilities. Nurses possess the capacity to educate others about the importance of hand hygiene (Larson, 2016). Accordingly, we structured our findings to the nursing process developed in 1958 by Ida Jean Orlando. The five sequential steps are assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation (Toney-Butler, 2019).

A literature review was conducted to assess evidence from qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies. We screened for relevance by reviewing the titles and abstracts of the papers and identified key studies pertaining to visitor hand hygiene. From there, we pursued references. We also consulted national and international infection control guidelines. We appraised the scientific literature using Dang and Dearholt’s (2018) five levels of evidence with Level 1 being the most stringent to develop and support our position on visitor hand hygiene (Dang & Dearholt, 2018). Because of ethical considerations in randomizing control groups, hand hygiene research in general has lagged compared to other healthcare research topics, with few randomized trials or epidemiologically rigorous observational studies. We included 55 studies spanning 17 years (2002-2019). These included 32 studies published during the last 5 years in professional peer reviewed journals and 23 seminal studies more than 5 years old (Appendix A). The studies included several different countries, healthcare systems, and settings (hospitals, long-term care facilities, and the community), with hospitals being the most frequent setting. Studies differed in focus, design, and methods. Research around visitor hand hygiene is scarce and little is known about research on visitor hand hygiene.

Results/Data/Outcomes

Studies showed effective education may increase the frequency of visitor hand hygiene, decrease the pathogens found on their hands, and, subsequently, decrease transmission across the healthcare settings (Cure & Van, 2015; Kundrapu et al, 2014; Pokrywka et al., 2017). Studies demonstrate a correlation between the lack of accountability and decreased hand hygiene adherence. Therefore, it is important to provide education and training for all who enter the healthcare setting regardless of role (Chassin et al., 2015a). Effective education may lead to client and worker engagement and increase worker hand hygiene adherence (Fox et al., 2015) and increase the frequency of visitor/family hand hygiene (Sunkesula et al., 2015). For example, effective education of parents regarding the importance of hand hygiene increased child welfare (Bowen et al., 2012).

Home hand hygiene habits are often not transferred to the healthcare setting (Barker et al., 2014; El Marjiya Villarreal et al., 2020). Hand hygiene practice is affected by time of day and availability and placement of hand hygiene supplies (Ellingson et al., 2014; Hobbs et al., 2016). Issues regarding hand hygiene adherence may include inaccessible supplies, irritating agents, lack of knowledge, forgetfulness, or lack of administrative leadership/support (O’Donnell et al., 2015). Barriers to implementing hand hygiene programs include lack of administrative support, workload, and negative attitudes. Ineffective education may also contribute to decreased hand hygiene (Knighton et al., 2018). Factors affecting the success of the education intervention for visitors may include clearly stated instructions and the visitor’s willingness and ability to adhere to the intervention (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b). For example, decreased cognitive ability or motor function, and presence of orthopedic devices or bandages may interfere with a person’s ability to perform hand hygiene (Hill et al., 2015; Burnett, Lee, & Kydd, 2008).

Recommendations

We recommend a multimodal strategy for the development of a visitor hand hygiene education program. First, assess the current rate of visitor hand hygiene and specific potential root causes for non-adherence (Chassin et al., 2015a). Once the root causes are identified, define the barriers specific to your facility or unit (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b). Identify themes impacting hand hygiene adherence and causes of non-adherence to define the problem (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b, Morales, 2017).

Next, plan interventions directed at your unique causes of hand hygiene failure as different causes require different remedial measures. Invest resources where needed and avoid wasting resources on problems you do not have. A “one size fits all” approach does not allow for customized improvement. Attempting to address hand hygiene globally with the same plan is not likely to address problems which differ among facilities (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b).

Leadership engagement is critical to facilitating a culture change

Leadership engagement is critical to facilitating a culture change (McInnes et al., 2014). Ensure your leadership is aware and supportive of hand hygiene with adequate resources (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b). Use a behavioral framework and recognized behavioral techniques to plan and execute interventions (Tuong, Larson, Armstrong, 2014). A bundled plan includes education, reminders, and feedback (Schweizer et al., 2014). Adopt an individualized plan, with videos, audio, and print materials to promote and sustain hand hygiene adherence (Morales, 2017, Tuong et al., 2014; Randle et al., 2014; McGuckin & Govednik, 2013). A digital support system may also promote and sustain hand hygiene adherence.

Finally, hold everyone accountable and responsible. Include hand hygiene to promote high quality care, a clean and safe environment, and visitor involvement (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b; Morales, 2017). Available resources which may be modified to target the visitor are listed in Appendix B.

Once the plan is implemented, it must be sustained for long-term benefits. We recommend incorporating and maintaining the following key points for successful implementation:

- Encourage healthcare visitor engagement. Emphasize personal responsibility and altruism (Busby et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2016; Morales, 2017; McInnes et al., 2014). Healthcare workers may need to assist visitors with hand hygiene as needed (Cheng et al., 2016; Sunkesula et al., 2015).

- Empower visitors and stakeholders to prevent transmission of pathogens (Seale et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2016; McInnes et al., 2014).

- Implement plans to target specific causes and to sustain improved performance. Change reminders periodically for effectiveness (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b).

- Build on the home behaviors of the visitor by exploring the community’s pre-existing attitudes and values regarding hand hygiene (Barker et al., 2014).

Address cultural beliefs; hand hygiene has both hygienic and ritualistic meanings. Assess and leverage the intrinsic value the community associates with hand hygiene to improve hand hygiene and decrease transmission. (Barker et al., 2014, Morales, 2017). Available resources which could be modified for visitor hand hygiene developed by Morales (2018) are listed in Appendix C.

Simplify education by breaking the information into components (Randle et al., 2014). Focus the education on the importance of hand hygiene and describe the available options (soap and water, alcohol-based handrubs, disposable wipes; Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b). Include the basics of infection prevention and the need for hand hygiene even when gloves or other personal protective equipment are used (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b; Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology [APIC], 2014). Additionally, explain the importance of avoiding touching the eyes, nose, or mouth (T-zone) to avoid self-contamination (Morales, 2017). Given the high frequency of mucosal contact, hand hygiene is essential to prevent pathogen transmission and self-inoculation (Kwok, Gralton, & McLaws, 2015).

There are five specific moments for visitor hand hygiene

Educational content must instruct visitors on when to perform hand hygiene. There are five specific moments for visitor hand hygiene adapted from the World Health Organization 5 Moments of Patient Hand Hygiene (WHO, 2009; Rai et al., 2017). These are: 1) Before and after touching the items in the healthcare setting (the client’s call button/remote, phone, service animals, etc.); 2) Before eating; 3) After using the toilet; 4) When entering or leaving the care area; and 5) In view of workers when they enter the care area to provide an unspoken reminder to workers to clean their hands before providing care. An example educational script is included in Appendix D.

Education should be provided in various forms to address levels of literacy, physical function, or sensory perception. Education may be provided individually and/or in groups (Knighton et al., 2018; Morales, 2017; Kwok et al., 2015). Since people may often forget to perform hand hygiene, verbal and visual cues may improve adherence (Chassin et al., 2015a; Morales, 2017; El Marjiya Villarreal et al., 2020). Verbal reminders may include automated audio prompts, hand hygiene champions, or reminders from others (Morales, 2017; Rai et al., 2017; Knighton et al., 2017). Automated systems may provide real-time reminders and generate feedback for quality improvement (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b). Champions may provide just in time coaching to encourage accountability and improve adherence. Champions may determine the cause of non-adherence to engage appropriate interventions (Chassin et al., 2015a). Visual reminders may include stickers, posters or pamphlets focused on targeted behavior change rather than simply convey information (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b; Morales, 2017; (El Marjiya Villarreal et al., 2020). Assess learning comprehension of education by having the learner repeat the key concepts verbally or by demonstration.

Select appropriate hand hygiene supplies as personal preference plays a role in adherence. Include several options such as soap (non-antimicrobial or antimicrobial) and water, disposable wipes, and alcohol-based handrubs when possible. Some may find disposable wipes difficult or unpleasant to use. Others may prefer push down pumps for alcohol-based handrubs (Chassin et al., 2015a; Morales, 2017; Rai et al., 2017; Knighton et al., 2017; Senol et al., 2014). Although handrubs with an alcohol concentration of 60% may decrease methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization, incomplete removal is common (Sunkesula et al., 2015). There is a lack of evidence to support the use of triclosan containing soap compared with alcohol- based handrubs, benzalkonium chloride, or chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG: Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b; Therattil et al., 2015). While the judicious use of 2% CHG may help to prevent transmission, chlorhexidine-free supplies should be available to prevent allergic reactions in sensitive people (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b).

Hand hygiene supplies must be accessible and easy to use. Ineffective placement of supplies decreases hand hygiene (Ellingson et al., 2014; Hobbs et al., 2016; O’Donnell et al., 2015). Visibility and accessibility of the supplies (upon entry to the facility or care areas, etc.) influence adherence (El Marjiya Villarreal et al., 2020). Those who may not easily access the sinks or wall-mounted dispensers may need accommodations (Ellingson et al., 2014; Cure et al., 2015; O’Donnell et al., 2015). Provide a convenient spot to place items as full hands also decrease adherence (El Marjiya Villarreal et al., 2020). Develop a maintenance plan to ensure supplies are always fully stocked (Chassin et al., 2015a).

Evaluate the intervention on a regularly scheduled basis (McInnes et al., 2014). Collect hand hygiene adherence data and report results accurately and frequently. Meaningful data include a target for improving adherence, such as role-based adherence (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b). Evaluate performance by incorporating a measurement system to audit adherence (McInnes et al., 2014). Commit to collecting and analyzing data using the same methods so the data be compiled across sites. Avoid the use of self-report as the primary method of hand hygiene adherence. Direct observations may measure adherence as well as identify barriers to hand hygiene. Inter-rater reliability must be assured. A combination of measurement approaches is appropriate and may be adjusted for your specific needs (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b; Cheng et al., 2016). Measurements of hand hygiene typically include healthcare workers and usually include entry and exit of care areas (“in and out”; Dawson & Mackrill, 2014). Likewise, an easy measurement may be visitor hand hygiene upon entry and exit from the care area (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b). An ultrasound-based location system or radio frequency identification badge may measure visitor hand hygiene in real-time (Srigley et al., 2014).

Reconceptualize non-adherence and develop progressive remediation for all (Chassin et al., 2015a; McInnes et al., 2014). A robust process improvement examines non-adherence to develop highly effective, targeted interventions focused on the prevalent causes at each facility. When there is a decline in visitor hand hygiene, the Targeted Solution Tool in Appendix B may provide specific recommendations to identify causes of non-adherence and increase adherence. Real-time displays of hand hygiene adherence may provide incentive for improvement (Chassin et al., 2015a; Chassin et al., 2015b). Consider recognition or rewards for those who model hand hygiene behaviors or improvements.

Visitor hand hygiene is an evidence-based strategy to reduce pathogen transmission

Visitor hand hygiene is an evidence-based strategy to reduce pathogen transmission. Specifically, healthcare associated infections are “never events,” preventable and egregious events which should never occur (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2008). Facilities are not reimbursed for costs associated with “never events.” Implementing a robust hand hygiene program which includes client, workers, and visitors may increase in the perception of healthcare workers’ caring, positively impacting client satisfaction and financial reimbursement. Despite universal acknowledgment hand hygiene is the single most effective way to prevent the spread of pathogens, visitor hand hygiene is seldom addressed. We presented strategies to develop interventions addressing barriers to visitor hand hygiene which do not hinder workflow or the visitation policy. The evidence-based multimodal strategy is affordable, practical, effective, acceptable, safe, and equitable. Finally, policy makers should create legislation mandating facilities provide education to visitors regarding hand hygiene.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the previously published Position on Healthcare Client Hand Hygiene authored by Katie Morales, PhD, RN, CNE (Chair), Kathleen Puri, MSN, RN, Shanina Knighton, PhD RN, Christine Greene, MPH, PhD, on behalf of the Healthcare Infection Transmission Systems (HITS) Hand Hygiene Workgroup. We would like to thank the Healthcare Infection Transmission Systems (HITS) Consortium for their support and all those who participated in the Workgroup on Hand Hygiene.

References

Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. (2014). Infection prevention basics. http://clients.site.apic.org/infection-prevention-basics/

Banfield, K. R., & Kerr, K. G. (2005). Could patients’ hands constitute a missing link? Journal of Hospital Infection, 61, 183–188.

Barker, A., Sethi, A., Shulkin, E., Caniza, R., Zerbel, S., & Safdar, N. (2014). Patients’ hand hygiene at home predicts their hand hygiene practices in the hospital. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 35, 585-588. doi: 10. 1086/675826

Barnett, A., Page, K., Campbell, M., Brain, D., Martin, E., Rashleigh-Rolls, R., Graves, N. (2014). Changes in Healthcare-Associated Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infections after the Introduction of a National Hand Hygiene Initiative. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 35(8), 1029-1036. doi:10. 1086/677160

Bowen, A., Agboatwalla, M., Luby, S., Tobery, T., Ayers, T., & Hoekstra, R. M. (2012). Association Between Intensive Handwashing Promotion and Child Development in Karachi, Pakistan: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166, 11, 1037.

Busby, S. R., Kennedy, B., Davis, S. C., Thompson, H. A., & Jones, J. W. (2015). Assessing patient awareness of proper hand hygiene. Nursing, 45(5), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000463667.76100.06

Burnett, E., Lee, K., & Kydd, P. (2008). Hand hygiene: What about our patients? British Journal of Infection Control, 9, 19-24.

Cao, J., Min, L., Lansing, B., Foxman, B., & Mody, L. (2016). Multidrug-resistant organisms on patients’ hands: A missed opportunity. The Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, 176(5), 705-706.

Chassin, M. R., Mayer, C., & Nether, K. (2015a). Improving hand hygiene at eight hospitals in the United States by targeting specific causes of noncompliance. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 41, 1, 4-12.

Chassin, M. R., Nether, K., Mayer, C., & Dickerson, M. F. (2015b). Beyond the collaborative: Spreading effective improvement in hand hygiene compliance. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 41, 1, 13-25.

Cheng, V. C. C., Tai, J. W. M., Li, W. S., Chau, P. H., So, S. Y. C., Wong, L. M. W., Ching, R. H. C., Ng, M. M. L., Ho, S. K. Y., Lee, D. W. Y., Lee, W. M., L., Wong, C. Y., Yuen, K. Y. (2016). Implementation of directly observed patient hand hygiene for hospitalized patients by hand hygiene ambassadors in Hong Kong. American Journal of Infection Control, 44, 6, 621-624.

Centers for Disease Control. (2019). Diseases and organisms in healthcare settings. http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/organisms/organisms.html#g

Centers for Disease Control. (2016). National and state healthcare-associated infections progress report. http://www.cdc.gov/hai/progress-report/index.html

Centers for Disease Control. (2015). Hand hygiene in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/patients/index.html

Centers for Disease Control. (2002). Guideline for hand hygiene in healthcare settings: Recommendations of the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA hand hygiene task force. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5116.pdf

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2008). CMS improves patient safety for Medicare and Medicaid by addressing never events. https: //www. cms. gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2008-Fact-sheets-items/2008-08-042.html

Cohen, C. C., Herzig, C. T. A., Carter, E. J., Pogorzelska-Maziarz, M., Larson, E. L., & Stone, P. W. (2014). State focus on health care-associated infection prevention in nursing homes. American Journal of Infection Control, 42, 4, 360-365.

Cure, L., & Van, E. R. (2015). Effect of hand sanitizer location on hand hygiene compliance. American Journal of Infection Control, 43, 9, 917-921.

Dang, D., Dearholt, S., Sigma Theta Tau International., & Johns Hopkins University. (2018). Johns Hopkins Nursing evidence-based practice: Model and guidelines. Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

Dawson, C. H., & Mackrill, J. B. (2014). Review of technologies available to improve hand hygiene compliance: Are they fit for purpose? Journal of Infection Prevention, 15, 222-228. doi:10. 1177/1757177414548695

El Marjiya Villarreal, S., Khan, S., Oduwole, M., Sutanto, E., Vleck, K., Katz, M., & Greenough, W. B. (2020). Can educational speech intervention improve visitors’ hand hygiene compliance? The Journal of Hospital Infection, 104(4), 414–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2019.12.002

Ellingson, K., Haas, J. P., Aiello, A. E., Kusek, L., Maragakis, L. L., Olmsted, R. N., Polgreen., P. M., Trexler, P., VanAmringe, M., Yokoe, D. S. (2014). Strategies to prevent healthcare-associated infections through hand hygiene. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 35, 937-960. doi:10. 1086/677145

Fox, C., Wavra, T., Drake, D. A., Mulligan, D., Bennett, Y. P., Nelson, C., Kirkwood, P., Jones, L., Bader, M. K. (2015). Use of a patient hand hygiene protocol to reduce hospital-acquired infections and improve nurses’ hand washing. American Journal of Critical Care, 24, 3, 216-224.

Healthy People 2020. (2014). Healthcare-associated Infections. https://www. healthypeople. gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/healthcare-associated-infections

Hill, J., Hogan, T., Cameron, K., Guihan, M., Goldstein, B., Evans, M., Evans, C. (2014). Perceptions of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and hand hygiene provider training and patient education: Results of a mixed method study of health care providers in Department of Veterans Affairs spinal cord injury and disorder units. American Journal of Infection Control, 42, 834-840. doi:10. 1016/j. ajic. 2014. 04. 026. 42

Hobbs. M. A., Robinson, S., Neyens, D. M., & Steed, C. (2016). Visitor characteristics and alcohol-based hand sanitizer dispenser locations at the hospital entrance: Effect on visitor use rates. American Journal of Infection Control, 44, 3, 258-262.

Istenes, N. A., Hazelett, S., Bingham, J. E., Kirk, J., Abell, G., & Fleming, E. (2011). Hand hygiene in healthcare: The role of the patient. American Journal of Infection Control, 9, E182 [abstract].

Knighton, S. C., Dolansky, M., Donskey, C., Warner, C., Rai, H., & Higgins, P. A. (2018). Use of a verbal electronic audio reminder with a patient hand hygiene bundle to increase independent patient hand hygiene practices of older adults in an acute care setting. American Journal of Infection Control, 46, 6, 610-616.

Knighton, S., McDowell, C., Rai, H., Higgins, P., Burant, C., & Donskey, C. J. (2017). Feasibility: An important but neglected issue in patient hand hygiene. American Journal of Infection Control, 45, 6, 626-629.

Kundrapu, S., Sunkesula, V., Jury, I., Deshpande, A., & Donskey, C. (2014). A randomized trial of soap and water hand wash versus alcohol hand rub for removal of Clostridium difficile spores from hands of patients. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 35(2), 204-206. doi:10. 1086/674859

Kwok, Y. A., Gralton, J., & McLaws, M. (2015). Face touching: A frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. American Journal of Infection Control, 43, 112-114. doi:10. 1016/j. ajic. 2014. 10. 015

Larson, E. (2016, April). Keynote address. 2016 national evidence-based practice conference – Changing landscapes: Contemporary issues influencing nursing care. Coralville, IA.

Massachusetts Hospital Association, (2016). Healthcare-associated Infections. Patient CareLink. http://patientcarelink. org/improving-patient-care/healthcare-acquired-infections-hais/

McGuckin, M., & Govednik, J. (2013). Patient empowerment and hand hygiene, 1997-2012. The Journal of Hospital Infection, 84, 3, 191-9.

McInnes, E., Phillips, R., Middleton, S., & Gould, D. (2014). A qualitative study of senior hospital managers’ views on current and innovative strategies to improve hand hygiene. BMC Infectious Diseases, 14, 1

Mody, L., Washer, L. L., Kaye, K. S., Gibson, K., Saint, S., Reyes, K., Cassone, M., Altamimi, S., Perri, M., Sax, H., Chopra, V., Zervos., M. (2019). Multidrug-resistant organisms in hospitals: What is on patient hands and in their rooms? Clinical Infectious Diseases, 69(11), 1837-1844.

Morales, K. (2017). Testing the effect of a resident-focused hand hygiene intervention in a long-term care facility: A mixed methods feasibility study. (PhD Dissertation). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (Mercer University No. 10615469).

Morales, K. (2018). Tools for monitoring hand hygiene in a long-term care facility. Infection Control. Tips. https://infectioncontrol. tips/2018/11/27/tools-for-hand-hygiene-intervention-monitoring-in-a-long-term-care-facility/

Morales, K., Puri, K., Knighton, S., & Greene, C. (2020). Position on healthcare client hand hygiene: Infection control tips. https://infectioncontrol.tips/2020/07/14/position-on-healthcare-client-hand-hygiene/?fbclid=IwAR1kW1V7Ccak012O8WsrpXqS7Ki5a0KZMt4rZ0NJ6e44TQOYXdOuZ83EaQg

National Council of State Legislatures. 2020. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and other healthcare-associated infections. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/healthcare-associated-infections-homepage.aspx#:~:text=Approximately%2027%20states%20have%20enacted,of%20the%20laws%20differs%20widely.

O’Donnell, M., Harris, T., Horn, T., Midamba, B., Primes, V., Sullivan, N., Shuler, R., Zabarsky, T. F., Deshpande, A., Sunkesula, V. C., Kundrapu, S., Donskey, C. J. (2015). Sustained increase in resident mealtime hand hygiene through an interdisciplinary intervention engaging long-term care facility residents and staff. American Journal of Infection Control, 43, 162-164. doi:10. 1016/j. ajic. 2014. 10. 018

Pokrywka, M., Buraczewski, M., Frank, D., Dixon, H., Ferrelli, J., Shutt, K., & Yassin, M. (2017). Can improving patient hand hygiene impact Clostridium difficile infection events at an academic medical center? American Journal of Infection Control, 45, 9, 959-963.

Rai, H., Knighton, S., Zabarsky, T. F., & Donskey, C. J. (2017). A randomized trial to determine the impact of a 5 moments for patient hand hygiene educational intervention on patient hand hygiene. American Journal of Infection Control, 45, 5, 551-553.

Randle., Arthur, A., Vaughan, N., Wharrad, H., & Windle, R. (2014). An observational study of hand hygiene adherence following the introduction of an education intervention. Journal of Infection Prevention, 15, 142-147.

Schweizer, M. L., Reisinger, H. S., Ohl, M., Formanek, M. B., Blevins, A., Ward, M. A., & Perencevich, E. N. (2014). Searching for an optimal hand hygiene bundle: A meta-analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 58, 2, 248-259.

Seale, H., Chughtai, A. A., Kaur, R., Phillipson, L., Novytska, Y., & Travaglia, J. (2016). Empowering patients in the hospital as a new approach to reducing the burden of health care-associated infections: The attitudes of hospital health care workers. American Journal of Infection Control, 44, 3, 263-268.

Şenol, V., Ünalan, D., Soyuer, F., & Argün, M. (2014). The relationship between health promoting behaviors and quality of life in nursing home residents in Kayseri. Journal of Geriatrics. doi:10. 1155/2014/839685.

Srigley, J. A., Furness, C. D., Baker, G. R., & Gardam, M. (2014). Quantification of the Hawthorne effect in hand hygiene compliance monitoring using an electronic monitoring system: A retrospective cohort study. British Medical Journal Quality & Safety, 23, 974-980. doi:10. 1136/bmjqs-2014-003080

Sunkesula, V., Kundrapu, S., Macinga, D. R., & Donskey, C. J. (2015). Efficacy of alcohol gel for removal of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from hands of colonized patients. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 36(2), 229– 231. https://doi. org/10. 1017/ice. 2014. 34

Sunkesula, V., Knighton, S., Zabarsky, T., Kundrapu, S., Higgins, P., & Donskey, C. (2015). Four moments for patient hand hygiene: A patient-centered, provider-facilitated model to improve patient hand hygiene. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 36(8), 986-989. doi:10. 1017/ice. 2015. 78

Sunkesula, V. C. K., Kundrapu, S., Knighton, S., Cadnum, J. L., & Donskey, C. J. (2017). A randomized trial to determine the impact of an educational patient hand-hygiene intervention on contamination of hospitalized patient’s hands with healthcare-associated pathogens. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 38, 5, 595-597.

Tejada, C. J., & Bearman, G. (2015). Hand hygiene compliance monitoring: The state of the art. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 17(4), 470.

Therattil, P. J., Yueh, J. H., Kordahi, A. M., Cherla, D. V., Lee, E. S., & Granick, M. S. (2015). Randomized controlled trial of antiseptic hand hygiene methods in an outpatient surgery clinic. Wounds, 27, 347–353.

Toney-Butler, T. J., & Thayer J. M. (2019). Nursing Process. https://www. ncbi. nlm. nih. gov/books/NBK499937/

Tuong, W., Larsen, E. R., & Armstrong, A. W. (2014). Videos to influence: A systematic review of effectiveness of video-based education in modifying health behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 2, 218-233.

Vaidotas, M., Yokota, P. K., Marra, A. R., Camargo, T. Z., Victor, E., Gysi, D. M., Leal, F., Santos, O. F., Edmond, M. B. (2015). Measuring hand hygiene compliance rates at hospital entrances. American Journal of Infection Control, 43, 7, 694-696.

Wallace, N., Cropp, B., & Coles, J. (2016). Insurance companies pay the price for HAIs. https://thehcbiz. com/losing-battle-hospital-acquired-infections-hcbiz-22/

World Health Organization. (2009). WHO Guidelines for hand hygiene in health care. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597906_eng.pdf

Appendix A

Levels of Evidence Based on Dang and Dearholt (2018)

Appendix B

Available Resources

Available resources which could be modified for visitor hand hygiene include:

Clean Hand Count for Patients [1]

The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare

Healthcare Improvement’s How to Guide

Patient Advocacy Materials, WHO Observation Forms

WHO Self-Assessment Framework,

[1] Centers for Disease Control. (2015). Hand hygiene in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/patients/index.html

Appendix C

Tools to Assess Hand Hygiene Values and Beliefs

Available resources which could be modified to assess visitor hand hygiene values and beliefs include:

Health Beliefs Related to Hand Hygiene Tool [1]

Participant’s Reaction to Hand Hygiene Intervention Questionnaire 2

[1] Morales, K. (2018). Tools for monitoring hand hygiene in a long-term care facility. InfectionControl.tips. https://infectioncontrol.tips/2018/11/27/tools-for-hand-hygiene-intervention-monitoring-in-a-long-term-care-facility/

Appendix D

Sample Educational Content

What can you do to prevent healthcare-associated infections? The good news is there are simple steps you can take to prevent infections. Clean your hands regularly, especially at these important times:

- Whenever you enter or leave the care area

- Whenever hands look or feel unclean

- Whenever there is a concern if hands are clean

- Before you eat or drink

- Before touching any broken skin

- Before any medical procedure

- Before contact with medical devices

- Before and after touching others

- After using the toilet

- After coughing or sneezing

To help prevent infecting yourself, avoid touching your eyes, nose, or mouth and always cough or sneeze into your elbow.

Ask if the medical devices are still needed each day. Also, ask about vaccines you need to stay healthy. While infections can be serious, taking these simple steps can help prevent infection.[1]

[1] Massachusetts Hospital Association, (2016). Healthcare-associated Infections. Patient CareLink. http://patientcarelink.org/improving-patient-care/healthcare-acquired-infections-hais/